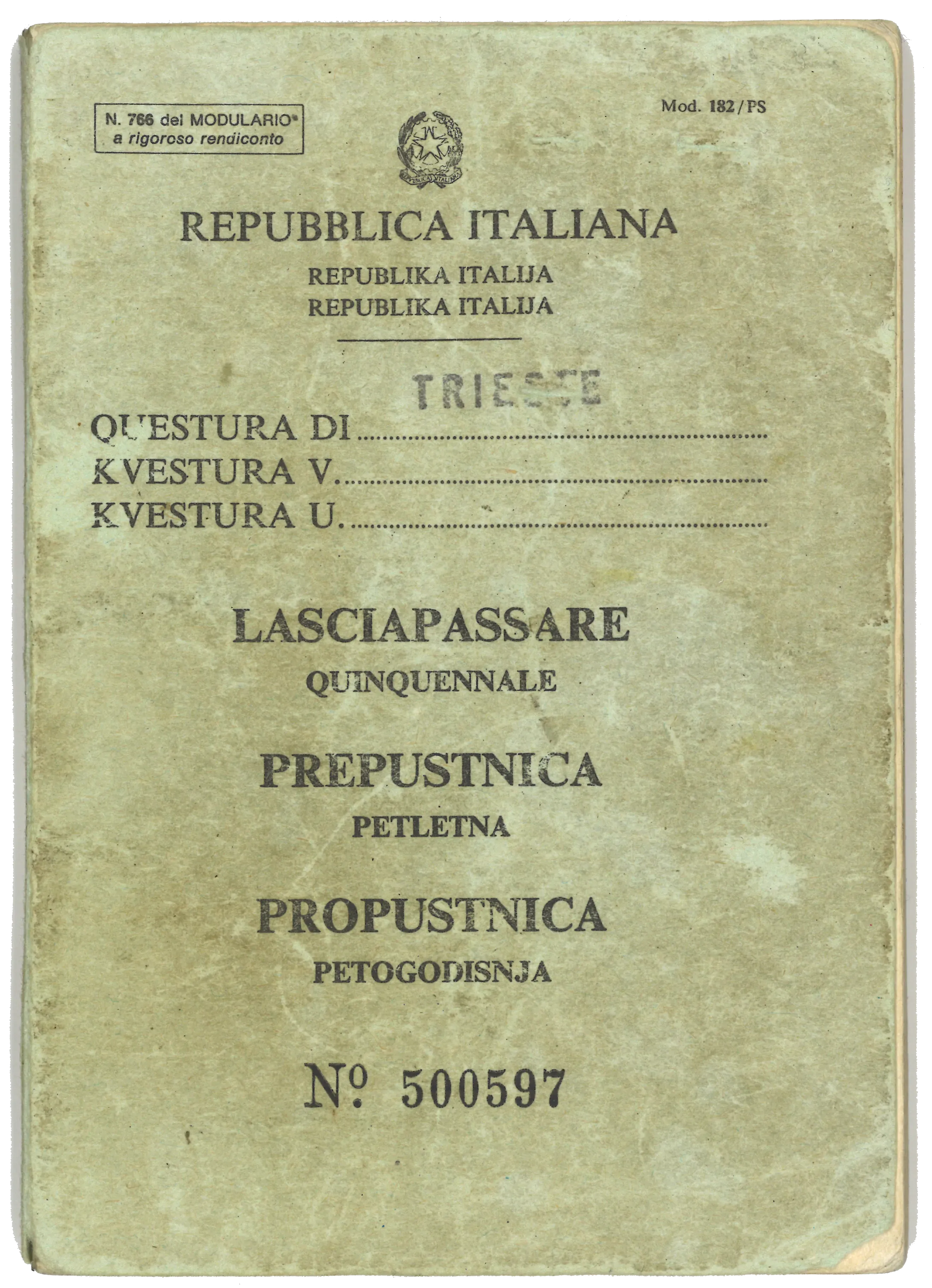

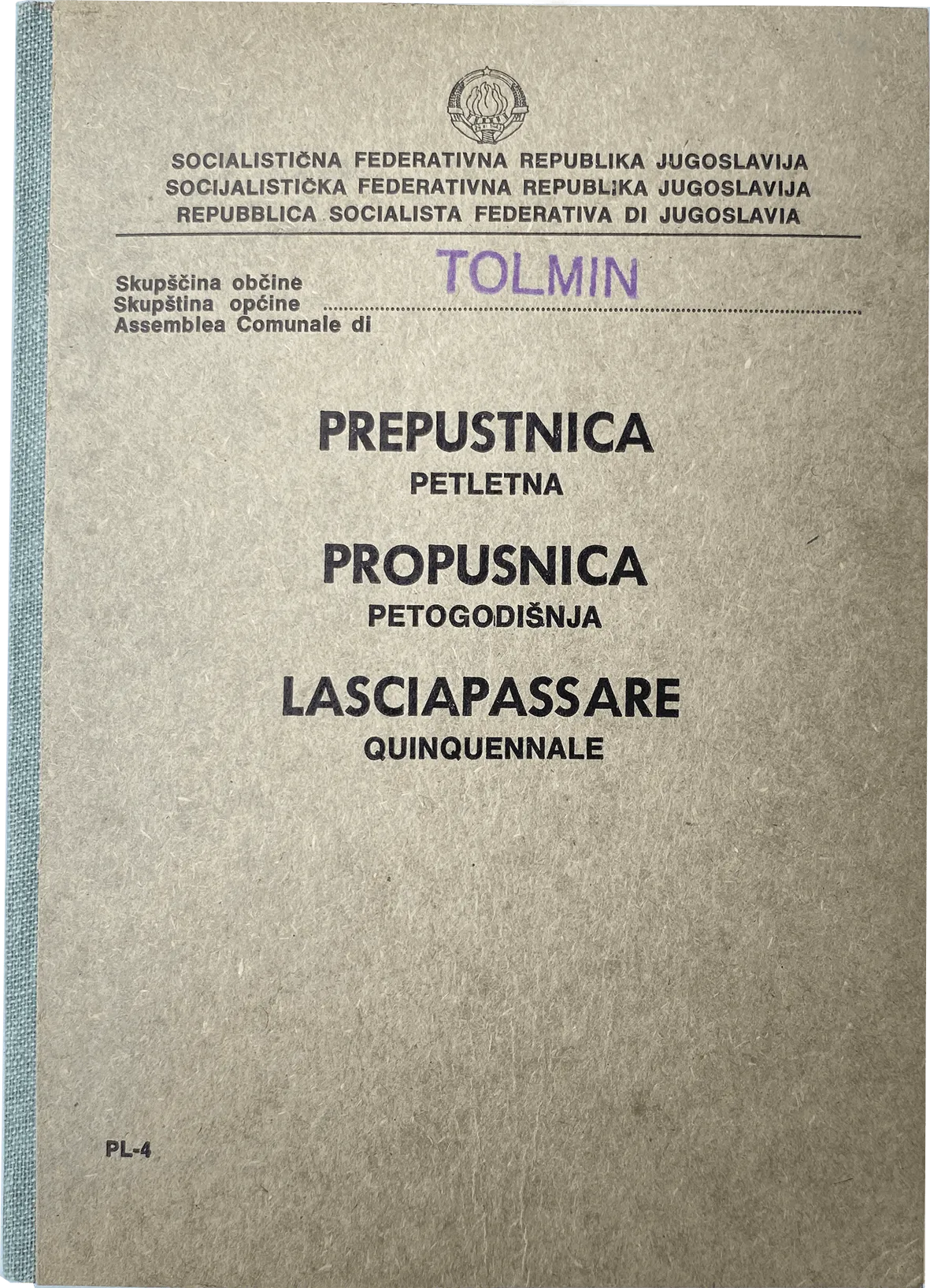

he laissez-passer was a bilateral, multilingual passport introduced to ease the limitations of living by the border by facilitating cross-border mobility to its holders. After the Second World War, state borders were almost hermetically sealed. Only residents who had property on the other side or those who lived in a ‘100-metre zone’ were allowed to cross. However, already in the mid-1950s the right to have this personal document in the Austro-Italian-Yugoslav border areas was extended to the population within a 10-kilometre area and later also applied to a larger zone. ‘Second category’ border crossing points were created for laissez-passer holders only.

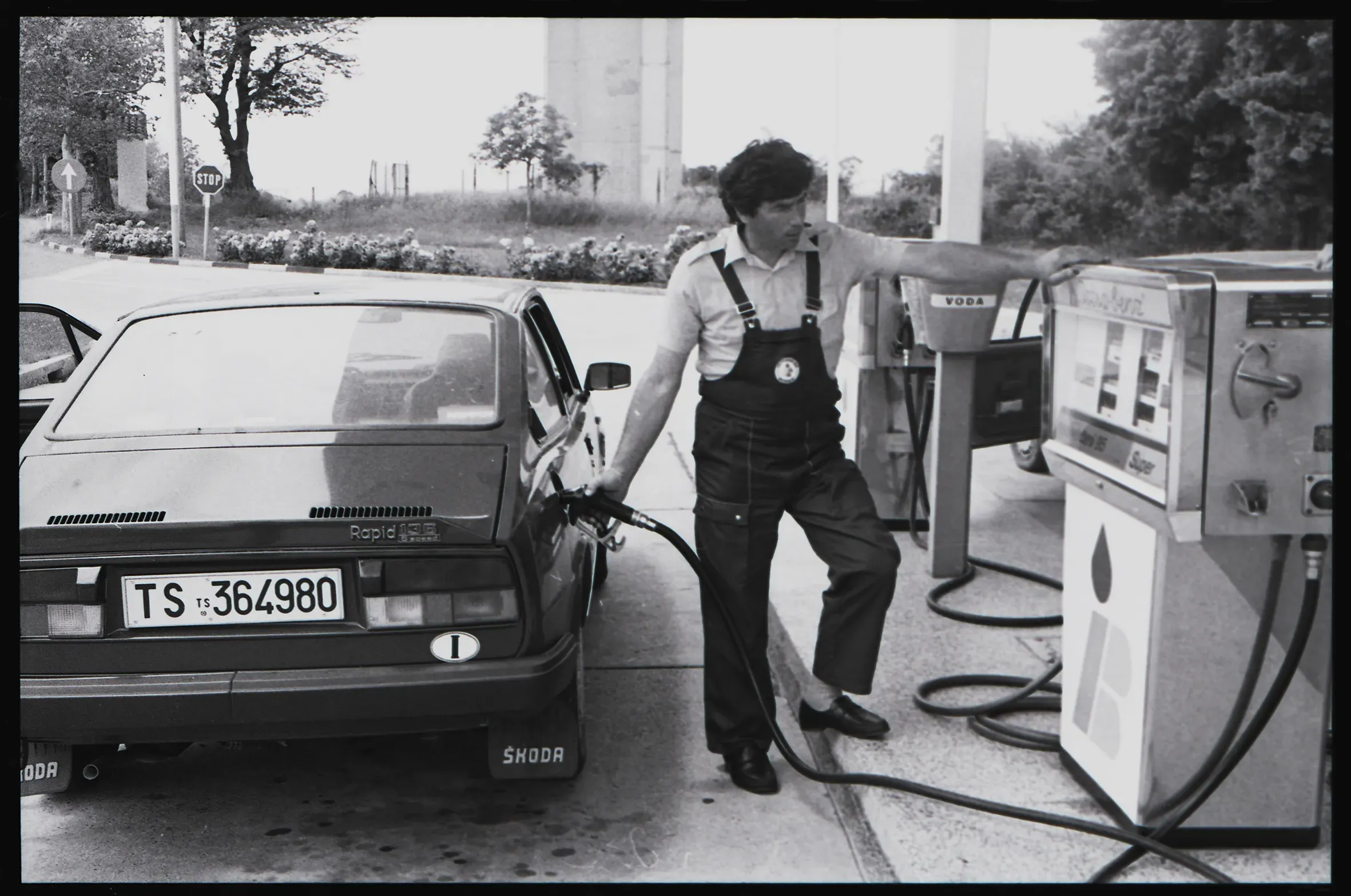

Yugoslav visas were gradually abolished, making cross-border mobility part of the quotidian for many borderland residents and a regular practice for many others. This increased mobility favoured the integration of larger territories that extended far beyond a narrow border strip. With the introduction of a borderless Schengen area the laissez-passer was rendered irrelevant. Will it be introduced again?

People

People

Places

Places

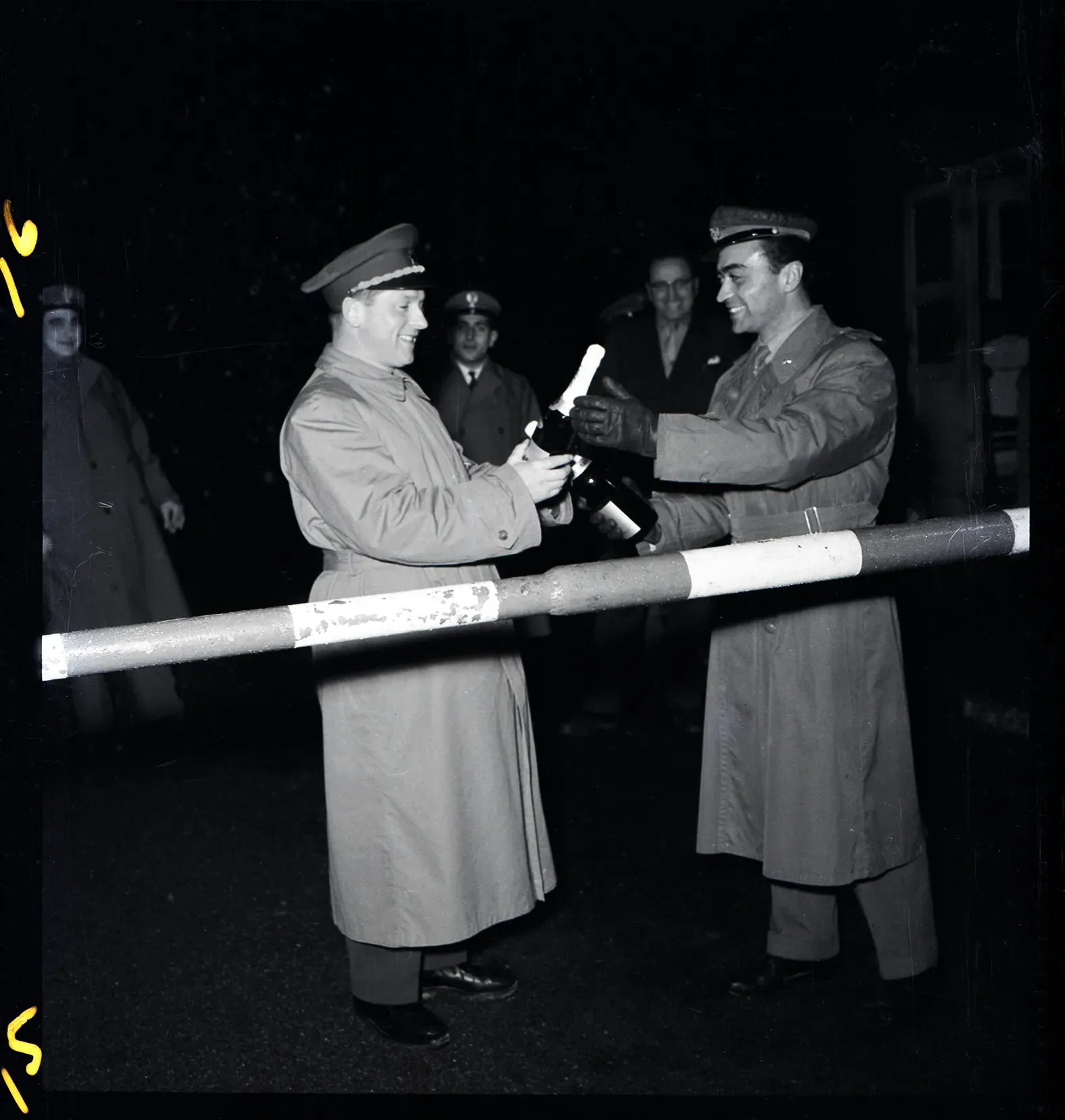

An exchange of New Year greetings at an Italian-Yugoslav border crossing point in Fernetiči/Fernetti in 1956. A series of postwar international and bilateral agreements turned crossing points into hubs and microcosms of trans-border practices.