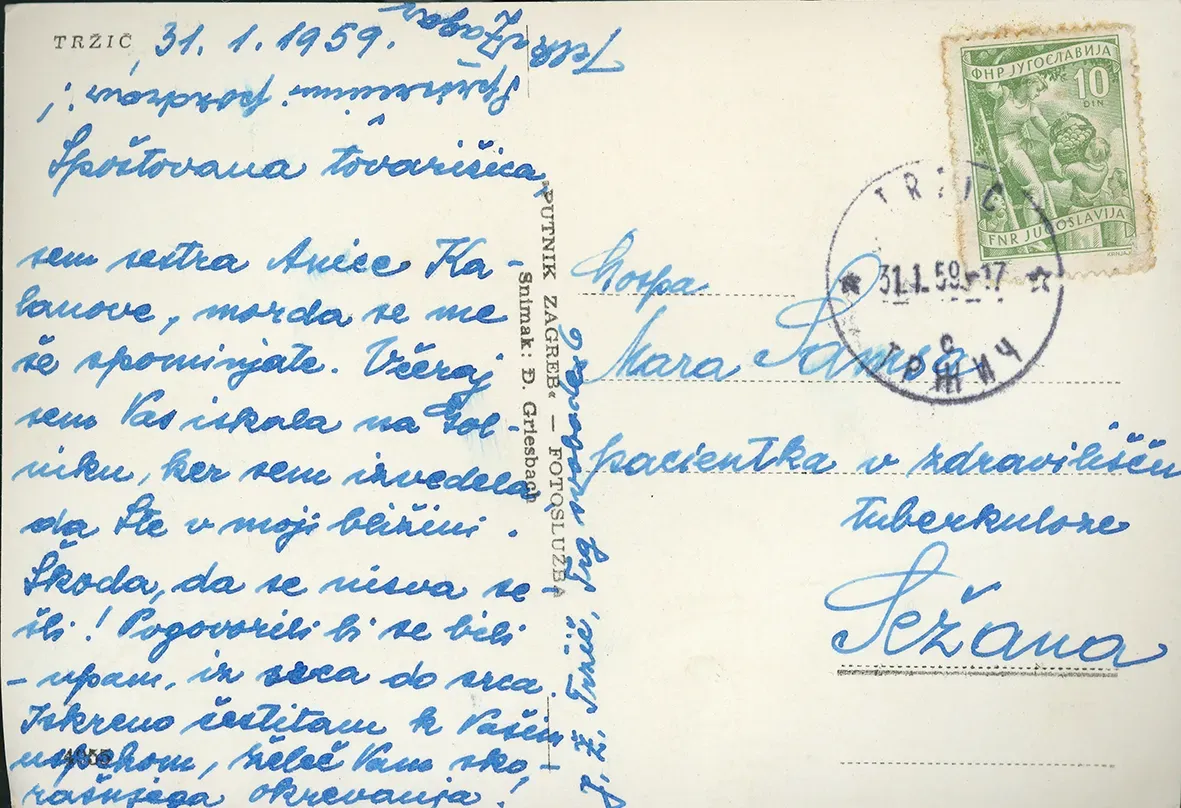

he case of health care is a good illustration of the porosity of the postwar Italo-Yugoslav border. Mobility took place in both directions, meeting the needs of both Italian and Yugoslav individuals and institutions. Seeking medical help in Yugoslavia was common, especially among pro-Yugoslav Slovene men and women from the area assigned to Italy in 1947. This was a valuable opportunity to receive medical care in their own language and to have access to medical services unavailable to them in Italy. This practice was encouraged by doctors from Italy who worked in the Slovenian healthcare system and became a reference for many Italian patients. Similar efforts were also made by doctors in Trieste and Gorizia, who maintained close friendships and professional contacts with their colleagues in Yugoslavia.

In this respect, it is worth noting that the Yugoslav space was considerably more favourable to women's reproductive rights than the Italian. At the end of the 1960s, a network of women's counselling centres was set up in a number of Slovenian towns like Nova Gorica, Sežana, Koper and elsewhere. Women from the Italian side of the border turned to them to legally obtain contraception. They could also go to health-care centres for abortions, which was legalised under special conditions in Yugoslavia in 1952 but banned in Italy until 1978.

People

People

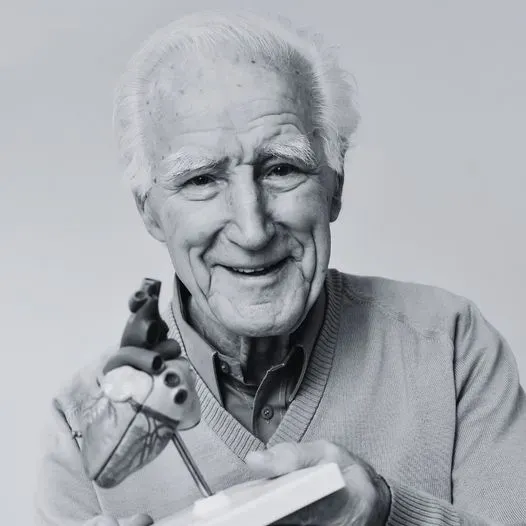

Boris Cibic (1921-2024), Slovenian cardiologist from Prosecco/Prosek near Trieste employed in the Dr. Peter Držaj Hospital in Ljubljana after the Second World War. He received professional training in Hamburg and London and attended professional meetings at home and abroad. He also established close contact with cardiologists in Trieste.

Places

Places

The Valdoltra Hospital in Ankaran/Ancarano was initially a specialised hospital for bone tuberculosis, later for orthopaedics. It was also vital for many patients from the region of Trieste.